John Baldessari, LA's great conceptual artist died early this year. Amongst his witty combined text and photographic artworks was a series contradicting the rules of photography, which he called ‘Wrong’. As part of this project he made large erasers (don’t say rubbers in the U.S.) which simply said ‘wrong’.

Baldessari was an artist who assiduously believed in the right to be wrong. One of his earliest conceptual works was to burn every canvas painted in his early career, turning the ashes into cookies for a cremation commemoration. Unlike many artists he possessed humility as well as a sense of humour. And a sense of wrong.

Many contemporary architects seem to be the opposite: adopting an artistic arrogance, rarely, if ever, admitting that they are wrong. Where does this arrogance come from? J’accuse Frank Lloyd Wright. Of all the great 20th C architects that are studied in architecture school Wright’s ambition and overweening self-belief stand out.

The stories are legendary. Some gobsmacking favourites are in Edgar Tafel's book ‘Apprentice to Genius, Years with Frank Lloyd Wright’ (1979). In 1957, FLW was interviewed on TV by Mike Wallace who asked him: “ As an architect, how would you like to change the way that we live?” FLW replied: “I would… like to change … what we live in, and how we live in it … and the letters we receive from our clients tell us how those buildings we built for them, have changed the character of their whole lives and their whole existence”.

This level of self-belief in design determinism may have been attractive in early modernism, but it’s wrong now. Today’s column is about what's wrong with architects’ arrogance in relation to their clients, particularly on residential projects (issues with building designs and construction can come later). Here’s some wrongs to be righted.

Clients

A client is a client. Not a patron. Architects are asked to solve a particular, and unique, problem for the client. By contrast patrons hire ‘starchitects’ to produce an ‘architect’s monument’ (usually to themselves), on an eye-watering budget. It’s wrong to confuse a client with a patron; the former is our stock in trade; it’s wrong to ever assume that they can be turned in to the latter.

The Project

Projects should evolve from listening to the brief and visiting the site. Absorb both before venturing anything like a possible individual creative solution. Too many projects start with architects strutting their work with glossy photos of past projects, digitally, on the web, in books. That’s asking to repeat yourself, not to be creative. Stop it, that’s wrong.

The Brief

The client's brief should be respected and cultivated. It is not sacrosanct but should be taken as a starting point and developed with the client, using the architect's interests and ideas. Many architects ignore the brief in favour of inveigling their own agendas. And that’s wrong.

Site and climate

It's not a tabla rasa in an air-conditioned bubble, as it is so often wrongly taken. You cannot ignore the surroundings (too modernist) or render it a blank canvas with a D12 bulldozer (too post-modernist). It’s real and messy and needs to be understood as such. Time to turn the clean sheet into a scribbled site analysis of McHargian proportions, addressing ‘country’, ‘culture’ and ‘climate’.

Style (aka design)

It’s important to have style, not to be in style. Well may we say that “style is dead”, because our contemporary times allow us, with all our tools and knowledge to move past styles. We can create unique propositions to purpose and place. Nevertheless, many architects are still looking backwards, selling the same solution, the same style, irrespective of the location. And that is wrong.

Budget

Architects are notorious for ignoring the client’s budget (assuming they ask about it), designing without the inhibition of how it will be funded. One colleague, only partly joking, says the first thing to do with a new client is to double the budget. We are all wronged and tarred by this brush of arrogance. Every project should set a budget and keep to it, despite what follows.

Builder

Architects are only a part of the total process and must rely on builders to complete any project, so architects are caught in a cleft stick: they must represent the client, but a single residential project may be the only project with that client, whilst they may want that builder for future projects. There is a conflict of interest, leaving working architects deeply conflicted, ethically and morally. And that is wrong.

Variations

Further reputational damage is done with architects reputedly running up huge costs at the client's expense through variations. But most architects I know report that variations in houses are most often driven by builders and clients, not the architects. Cost overruns come from a desire to change or improve the building as it goes along and the opprobrium is worn by the architects because they are not paid sufficiently well to properly manage the building process in an independent way, and that is wrong.

Respect

Architects should treat each other with far more respect. When asked to take over another’s design architects have a responsibility to notify the original author, not only as a courtesy but to protect moral rights. Even more so when the building has a record or history. But younger architects seem too often keen to compete for the project in isolation. And that is wrong

Design review panels

Another loss of collegial respect occurs in design review panels. Too many retired architects, at the end of their careers, take up positions having never lost the very poor crit culture fostered at their architecture school. They push their own ideas without listening to the architect’s ideas of brief and site, and it's the wrong approach

Fees

Finally, the thing that most architects get most wrong: not enough fees. The causes are many: no reliable professional guide for the public; architects undervaluing their time; architects cannibalising projects with underquoting. Solutions will take another column, but for now two possibilities: hourly rates match the clients (take that you lawyers) and follow droit de suite, see here.

Bottom Line

If residential architects listen to and communicate better with their clients, respond to the brief and site more assiduously, and then transparently manage their client’s money better through the building process, treating the contract as a whole, then they could expect to be paid the fees they undoubtedly deserve.

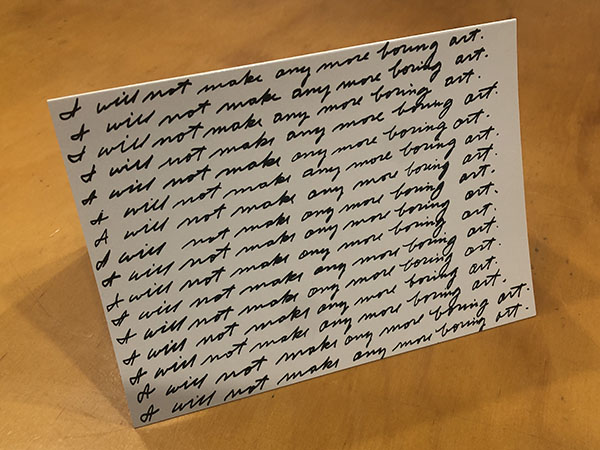

And here’s a final suggestion on a calling card from John Baldessari. For those that started reading last October 2019, this is Tone on Tuesday #50, a year’s worth!

For those that started reading last October 2019, this is Tone on Tuesday #50, a year’s worth!

Tone Wheeler is principal architect at Environa Studio, Adjunct Professor at UNSW and is President of the Australian Architecture Association. The views expressed here are solely those of the author and are not held or endorsed by A+D, the AAA or UNSW. Tone does not read Instagram, Facebook, Twitter or Linked In. Sanity is preserved by reading and replying only to comments addressed to toneontuesday@gmail.com.